Supplementary Information on sauropod neck sexual selection

15th May 2011

This page contains unofficial supplementary information for the

paper:

-

Taylor, Michael P.,

David W. E. Hone,

Mathew J. Wedel

and

Darren Naish.

2011.

The long necks of sauropods did not evolve primarily through

sexual selection.

Journal of Zoology,

Early View (Online Version of Record published before inclusion in

an issue).

doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00824.x

[PDF]

The following high-resolution versions of the figures from the

sauropod neck sexual selection paper are for the benefit of

scientists. Feel free to reproduce or modify these for use in

scientific (i.e. peer-reviewed) literature. Please do not

reproduce these in other non-scientific contexts without explicit

permission from the authors. (We'll proabably give permission, but

you need to check.)

|

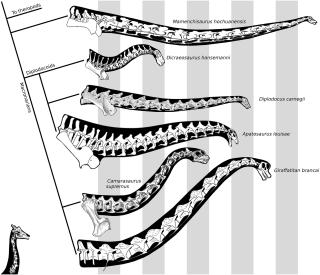

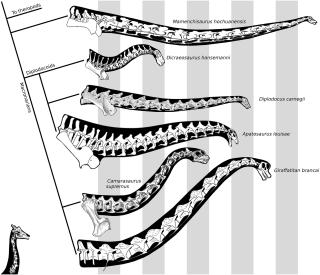

Figure 1.

Sauropod necks, showing relationships for a selection of species, and

the range of necks lengths and morphologies that they encompass.

Phylogeny based on that of Upchurch et al. (2004: fig. 13.18).

Mamenchisaurus hochuanensis (neck 9.5 m long) modified from

Young & Zhao (1972: fig. 4); Dicraeosaurus hansemanni (2.7 m)

modified from Janensch (1936: plate XVI); Diplodocus carnegii

(6.5 m) modified from Hatcher (1903: plate VI); Apatosaurus

louisae (6 m) modified from Lovelace, Hartman & Wahl (2008:

fig. 7); Camarasaurus supremus (5.25 m) modified from Osborn &

Mook (1921: plate 84); Giraffatitan brancai (8.75 m) modified

from Janensch (1950: plate VIII); giraffe (1.8 m) modified from

Lydekker (1894:332). Alternating grey and white vertical bars mark 1 m

increments.

|

|

|

Figure 2.

Long necks often serve multiple functions, as demonstrated here by

Galapágos giant tortoises Geochelone nigra. (a) Use of the

long neck for high browsing is commonly practized by terrestrial

testudines. Based on a photograph in Moll (1986:74-75). (b) Use of

the long neck in establishing dominance. The two tortoises shown in

the illustration were photographed on Santa Cruz Island: the

dome-shelled animal on the right belongs to the native

form G. n. porteri while the saddlebacked animal

at left represents the Española form G. n.

hoodensis. Based on a photograph in Fritts (1984: Fig. 2).

|

|