6th May 2008

Michael P. Taylor

Palaeobiology Research Group,

School of Earth and Environmental Sciences,

University of Portsmouth,

Burnaby Road,

Portsmouth PO1 3QL,

UK.

<dino@miketaylor.org.uk>

The sauropod dinosaurs are among the most iconic of all prehistoric animals, with their distinctive small heads, long necks, huge torsos and long tails. The first genera now recognised as sauropods, Cardiodon and Cetiosaurus, were named by Owen in 1841, only 17 years after the first dinosaur was named and a year before the term "dinosaur" was coined. However, Cardiodon was based on a pair of uninformative teeth; and Cetiosaurus, from the scant remains then available, was initially interpreted as an immense aquatic crocodilian. The type humerus of Pelorosaurus was the first sauropod bone to be interpreted as that of a terrestrial animal, by Mantell in 1850, due to its possession of a medullary cavity, but it was not then recognised as related to Cetiosaurus. The two presacral vertebrae on which Seeley founded Ornithopsis in 1870 were thought to be pterosaurian due to their light construction and pneumatic foramina, features not then known in any terrestrial animal.

The much more complete remains of the new species Cetiosaurus oxoniensis, described by Phillips in 1871, began to cast light on the sauropod body plan, suggesting that sauropods were dinosaurs rather than crocodilians. But it was not until the description of the American sauropods Apatosaurus and Camarasaurus in 1877 that anything like a complete sauropod skeleton was found. In the same year, Lydekker named Titanosaurus on the basis of isolated tail vertebrae from India, becoming the first Gondwanan sauropod. Marsh named Diplodocus the next year, and in the same paper created the taxon Sauropoda to hold these genera.

Traditionally, sauropods were considered amphibious, requiring water to support their great mass, although Phillips suggested otherwise as early as 1871 and Riggs argued forcefully for terrestriality in 1904. Many independent lines of research now show that sauropods were predominantly terrestrial: they had compact feet unsuited for swamps, tall and relatively narrow torsos adapted for weight bearing, and pneumatised skeletons that greatly reduced their weight. Furthermore, sauropod fossils are found primarily in terrestrial sediments.

Early reconstructions of sauropod skeletons, such as Marsh's 1883 Brontosaurus, correctly positioned the legs upright. However, Tornier (1909) in Germany and Hay (1910) in America favoured a lizard-like sprawl in which the humerus and femur project at right-angles to the body -- a suggestion soundly refuted by Holland (1910). Neck posture, however, continues to be controversial. Although Marsh's Brontosaurus reconstruction showed a nearly horizontal neck, the neck of Christman's Camarasaurus in Osborn and Mook's 1921 monograph was inclined upward, and Janensch (1950) reconstructed the neck of Brachiosaurus brancai nearly vertical. Recent computer simulations of cervical joints favour horizontal neck postures; but these studies remain open to interpretation, and other lines of evidence, both mechanical and ecological, support high browsing.

New sauropod discoveries continue to expand our knowledge, with half of all known sauropod genera having been named in the last two decades. These include the spiked Amargasaurus, huge Argentinosaurus, wide-mouthed Nigersaurus and short-necked Brachytrachelopan, indicating that sauropods were far more diverse than previously recognised.

References

- Cope, E. D. 1877. On a gigantic saurian from the Dakota epoch of Colorado. Paleontology Bulletin 25:5-10.

- Hay, O. P. 1910. On the manner of locomotion of the dinosaurs, especially Diplodocus, with remarks on the origin of birds. Proceedings of the Washington Academy of Science 12:1-25.

- Holland, W. J. 1910. A review of some recent criticisms of the restorations of sauropod dinosaurs existing in the museums of the United States, with special reference to that of Diplodocus carnegiei in the Carnegie museum. American Naturalist 44:259-283.

- Janensch, W. 1950. Die Skelettrekonstruktion von Brachiosaurus brancai. Palaeontographica (Suppl. 7) 3:97-103 and plates VI-VIII.

- Lydekker, R. 1877. Notices of new and other Vertebrata from Indian Tertiary and Secondary rocks. Records of the Geological Survey of India 10:30-43.

- Mantell, G. A. 1850. On the Pelorosaurus: an undescribed gigantic terrestrial reptile, whose remains are associated with those of the Iguanodon and other saurians in the strata of Tilgate Forest, in Sussex. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 140:379-390.

- Marsh, O. C. 1877. Notice of new dinosaurian reptiles from the Jurassic formation. American Journal of Science and Arts 14:514-516.

- Marsh, O. C. 1878. Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs. Part I. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 16:411-416.

- Marsh, O. C. 1883. Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs. Pt. VI. Restoration of Brontosaurus. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 27:329-304.

- Osborn, H. F., and C. C. Mook. 1921. Camarasaurus, Amphicoelias and other sauropods of Cope. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, n.s. 3:247-387 and plates LX-LXXXV.

- Owen, R. 1841. A description of a portion of the skeleton of the Cetiosaurus, a gigantic extinct Saurian Reptile occurring in the Oolitic formations of different portions of England. Proceedings of the Geological Society of London 3:457-462.

- Phillips, J. 1871. Geology of Oxford and the Valley of the Thames. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 529 pp.

- Riggs, E. S. 1904. Structure and relationships of opisthocoelian dinosaurs. Part II, the Brachiosauridae. Field Columbian Museum, Geological Series 2, 6:229-247.

- Seeley, H. G. 1870. On Ornithopsis, a gigantic animal of the Pterodactyle kind from the Wealden. Annals of the Magazine of Natural History, series 4, 5:279-283.

- Tornier, G. 1909. Wie war der Diplodocus carnegii wirklich gebaut? Sitzungsbericht der Gesellschaft naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin 4:193-209.

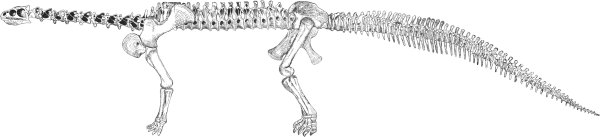

Camarasaurus supremus Cope 1877, skeletal reconstruction by John A. Ryder. This reconstruction was executed in 1877, the same year that the first Camarasaurus remains were discovered, and is the earliest known attempt to reconstruct a sauropod skeleton. It was first exhibited at a meeting of The American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on December 21, 1877, and first published as a reduced figure by Mook (1914). Reproduced from Osborn and Mook (1921: plate LXXXII).

(The abstracts booklet for this conference was much better than for most: the abstracts are twice as long, and so contain actual information rather than just an advert for the talk, they are allowed to have references, and they get a figure, too. In fact, they're like tiny, tiny papers.)